Blog

Sustainable Defined: Part I

August 14, 2013What would design be like if we saw ourselves as part of nature instead of separate from it?

This is the question I hope to address in my next series of posts. First, let’s be clear about the definition(s) I am using when I talk about sustainability. Two definitions that have influenced my thinking are addressed in this post, and three more that have become more influential in the world of sustainability that I will take up in the next one.

1. What is sustainability? The clearest and most concise articulation I know of the goal and work of sustainability comes from Professor David Orr in his book Ecological Literacy. It is a definition that we can use to consider any action we undertake as humans:

“[sustainable design] is the careful meshing of human purposes with the larger patterns and flows of the natural world…”

The idea that sustainability is an aspiration rather than a defined state is consistent with what we know, and how little we know, really, about how nature works and how we humans are really supposed to fit into it—especially seven billion of us, along with our stuff.

2. What drives sustainability? At a conference in Maastricht in 2000, my friend and mentor Hal Levin said (and I paraphrase) “Sustainability is really about a change in consciousness.” Having been grappling with a host of technical sustainability strategies and policies at the time, I realized at that moment that the aspiration of a sustainable world, like the aspiration of peace, is what allows any material changes to happen. You can’t have Orr’s definition unless you are open to it. This is not to say that one can’t legislate or design better environmental performance of the things we make—only that sustainability comes from the values and consciousness that we bring to it.

Next up, I will take on the Brundtland and People-Planet-Profit definitions, as well as the essence of McDonough Braungart’s Cradle to Cradle…

Inconceivable! Uranium, Fracking, and the Limits of Engineering

July 22, 2013Whether or not we agree that nuclear energy should be part of the nation’s energy future, the risks of uranium mining—recently proposed to restart in Virginia—must be clearly articulated for the public and our elected officials. Even Virginians, many of whom loathe the very concept of regulation, welcome the idea that uranium mines should be regulated (or banned).

Risk assessment is accepted practice, but the assumptions behind it are technical and rarely shared beyond panels of experts. Risk assessment does not seem to deal very well with the concept unthinkable disaster because it is, well, unthinkable. But unthinkable disasters seem to have become rather common in recent years. Maybe we need new approaches to determine whether or not to pursue dangerous industrial projects.

Industrial technologies, including nuclear reactors, uranium mines, and hydraulic fracturing, are all designed to certain performance standards, and are engineered using risk assessment and life-cycle cost analysis. For example, the lifespan of a uranium mine tailings pit liner is estimated to be 200 years. However, the radioactivity lasts 100,000 years*. That suggests that someone is going to have to replace the liners 500 times. Is that cost factored into the budget? Who will administer the 100,000 year waterproofing subcontract? It is unlikely that anyone is entertaining such questions, or that a clear path of accountability has even been outlined. It’s beyond our ability to imagine such a time frame.

Then there is the question of leaks during the 200-year “life” of the pool liner. As a registered architect for over 25 years I am deeply familiar with building codes, engineering design, construction cost estimating, cost-benefit analysis, and construction project management of large, complicated structures, and I can tell you one thing with absolute certainty: roofs eventually leak. True, engineering design for nuclear reactors, mines and refineries is far more intensive and far less likely to fail than say, an average concrete swimming pool—but the law of gravity still applies (as do many other laws, including Murphy’s).

With each new natural or engineering disaster—Valdez, Deepwater, Three Gorges, Chernobyl, Bhopal, Katrina, Fukushima, Sandy—we get a sense of how vulnerable we actually are. Like Wally Shawn’s character in The Princess Bride we stand and stare, mouths agape, and exclaim, “Inconceivable!” But the effects of disasters on human engineering works are, to a large extent, conceived in every design. Engineering uses the concept of “safety factor,” a multiple of the design performance of a material of system to establish a reasonable assurance that some combination of small errors and/or unusual stresses will not cause a failure. It’s adding a belt to the suspenders. Risks are minimized, and designs upgraded, to the extent that they satisfy technical panels, insurers and regulators. We design skyscrapers to withstand earthquakes and sometimes bombs, but we will never be able to make a high rise withstand a commercial jet with a full tank. It’s unthinkable. Risk assessment is part of how things get done in the real world; it’s how we give ourselves a sense of security in a world where large engineering works reasonably well. It is encouraging that society is today asking for a better accounting of potential external upstream and downstream effects of industrial practices. Some of those practices have a very small risk of a very large, long-term, human, and GDP-rocking cost.

So maybe the idea of risk itself has limits. “Inconceivable” risks are certainly less likely to be included in studies and policy. An important paper published by the Hamilton Project last year** quantified and compared the true cost of all energy sources, but the authors were unable to arrive at an average external cost for nuclear accidents and upstream environmental effects (so they added a footnote instead). What if, instead of putting a price tag on certain disastrous events that are irreversible, we don’t take the risk in the first place? It is a lot easier to decide not to mine uranium than to do 100,000 years of risk analysis.

PS to my great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren: Don’t forget to change the uranium tailings liners. And make sure the waterproofing subcontractors don’t miss a spot.

* Bill Spieden January 27, 2013 Guest Column to Daily Progress, Charlottesville, VA

**http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/paying_too_much_for_energy_the_true_costs_of_our_energy_choices/

FUKUSHIMA UPDATE and scary picture: http://fukushimaupdate.com/fukushima-is-still-leaking-radiation-and-tepco-is-still-clueless/

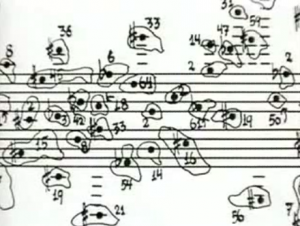

Begin Anywhere

July 15, 2013Those words are John Cage’s advice for artists paralyzed by not knowing where (or how) to start. I’m starting here, BEFORE retooling my website around my current goals (getting back into a architecture & sustainability at a large firm). I never got started blogging and instead wrote some longer essays that became too cumbersome to post or publish. I plan to break some of those ideas down into smallish (300 word) posts.

Bruce Mau’s Incomplete Manifesto for Growth (1998), which incorporates Cage’s point, is one way I know I am a designer. http://www.brucemaudesign.com/4817/112450/work/incomplete-manifesto-for-growth

It’s a great description of what it is like to solve problems creatively and full of some of the little tricks artists use to get to the state of mind where they know they can be most effective.

Competitive athletes know when they are “in the zone,” where their movements and focus results in a kind of unconsciously high performance. They may not know how to GET in the zone, it’s Zen-like, but they know when they are there. A good design process is like that. In addition to “practice, practice, practice,” finding the way back to The Zone requires one to develop daily habits that make a successful outcome more likely.

Future posts will be about a lot of different subjects–architecture, sustainability, culture, technology, politics etc.– but the posts are also about beginning somewhere/anywhere to be in a position for good things to happen.